Baby Steps in Understanding the Elliptic Curve

The area of an ellipse is given by $\pi a b$, where a and b are half-width and half-height – straightforward enough. But what about the arc length of an ellipse? Faced with a problem infinitely more complex than that of a circle, here mathematicians’ problems begin.

Quick intuition regarding arc length of parameterized curves easily lead us to integrals of the form $s=\int^{2\pi}_0 \sqrt{1-e^2 \cos ^2 t }dt$. But loads of integrals composed of elementary functions cannot be reduced to elementary form. When those pesky integrals arise in important contexts, mathematicians define new functions to confront them without algebraic hassle.

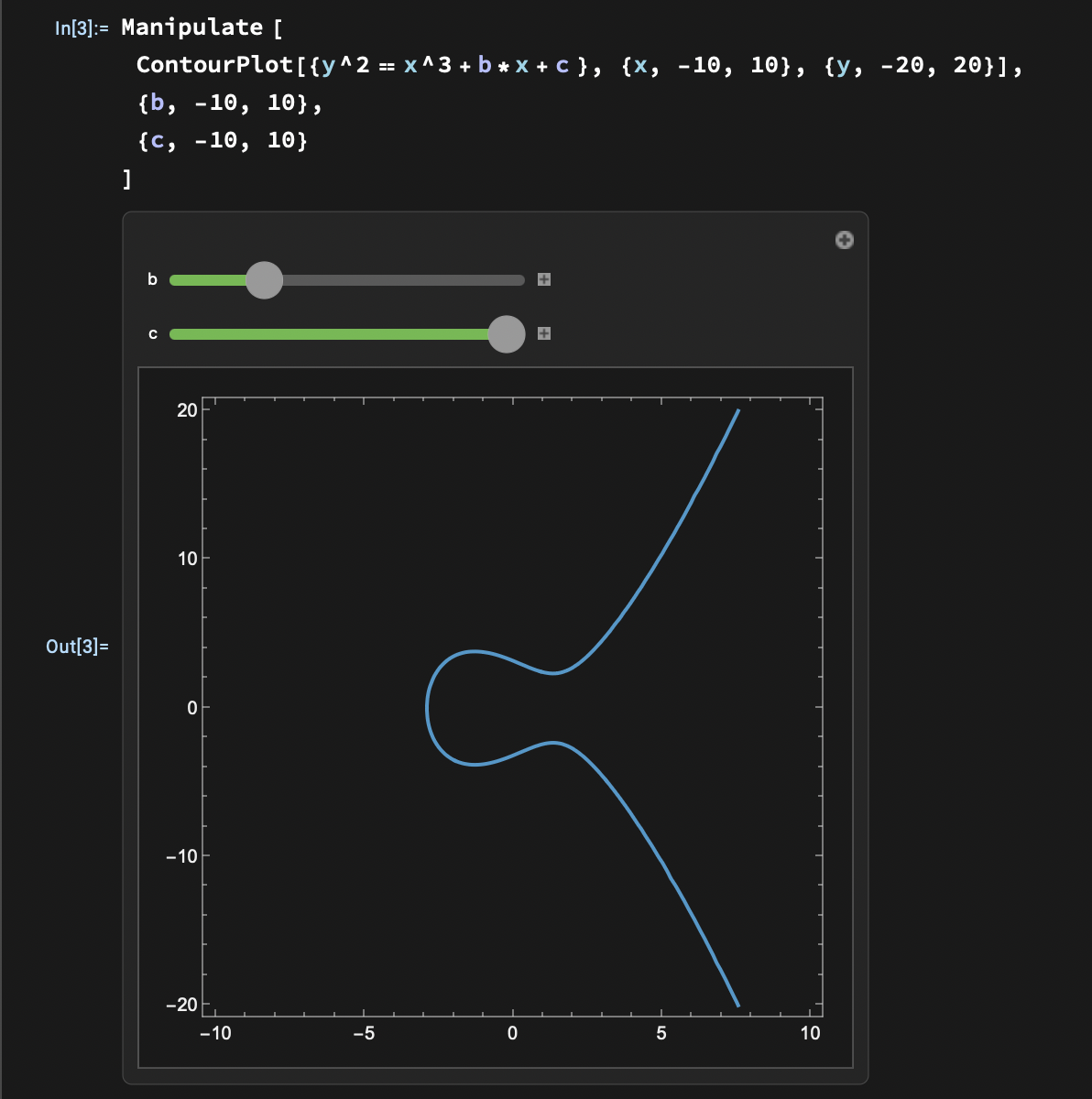

Apparently, a whole new family of integrals arise from the study of ellipses’ arc length. While handful of the new elliptic integrals are detached from the geometric ellipse itself, the names stuck. The near-generic term was also given to a mysterious curve constructed from inverting the elliptic integrals. The elliptic curve $y^2=x^3+bx+c$, in all its glory, is plotted below.

I dedicated precious time to justify the curve’s etymology, when no geometric ellipse shines in an odd family of curves. But soon enough, we will have to escape plots and geometry altogether and dive into number theory.

But before we leave the familiar $\mathbb{R}^2$ realm of plots, something other than etymology should be justified – what makes them so interesting. The very reason elliptic curves are studied is because they are an intellectual playground where many theories converge to and diverge from. One of those theories is the study of groups, (loosely) a set that defines operations among its elements. Here the elements are points lying on $y^2=x^3+bx+c$.

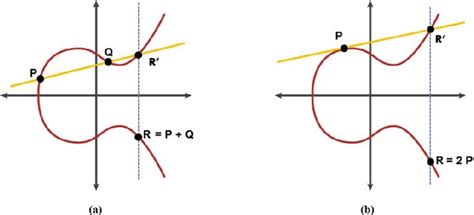

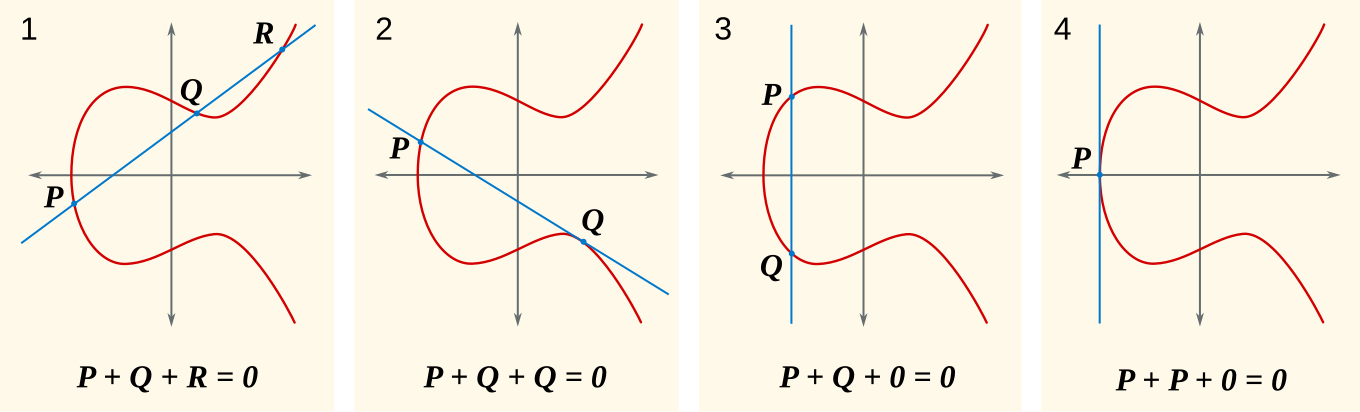

What does it mean to add points on a curve? Note that addition is a matter of clever definitions, chosen so that familiar laws of arithmetic do not crash even when entities are too abstract to leave crystal clear intuitions. The following diagram taken from Wikimedia and from A Robust and Hybrid Cryptosystem for Identity Authentication (Takieldeen & Elkhalik 2021) best show how points are added.

Take two points $P$ and $Q$ on an elliptic curve $E$. Define $P+Q$ by the point of intersection of line $PQ$ and $E$ flipped along the x axis. If $P$ and $Q$ are the same points, $P+P = 2P$ involves (this time intuitively) the tangent line at P.

We encounter an important problem. The premise of groups is that any operation must yield a result that is also part of the group, i.e. point addition must always produce precisely one point on the curve. This is not the case if and only if the line connecting two operand points is vertical. The mathematical genius of the theory resolves this issue by introducing a point at infinity $0$ (or $O$) as the identity element. If we denote $X$ reflect along the x axis as $-X$, $X+(-X) = X-X := 0$. Note that for any point P, $P+0 := P$. Using these rules, points on the elliptic curve can be added and subtracted without contradiction. More formally, they form a group.

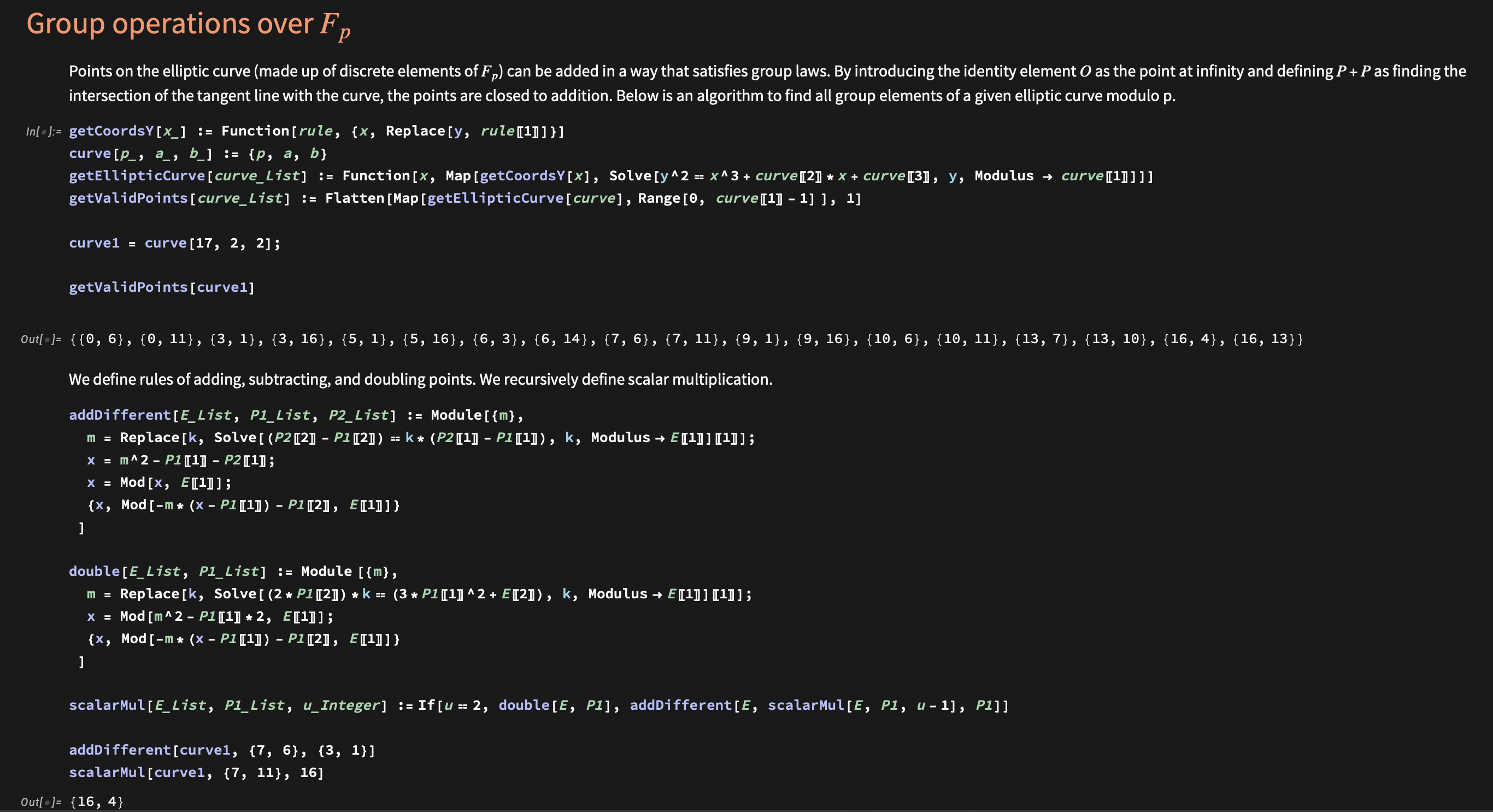

Interestingly, they still do when points go completely discrete. By discarding plots and using modular mathematics, elliptic curves are more abstractly defined as $E: y^2 \cong x^3+bx+c \pmod{p}$ over the numbers ${0, 1, 2, 3, .., p-1}$. Now, points composed of integers modulo $p$ can be added in the same manner, but this time with algebraic formulas that replace intersections and reflections. A patchy Mathematica demonstration is shown below. The process is simple, perhaps even unimportant for our purposes.

Moving to the discrete world of integer elliptic curves has a distinct advantage. They can be stored, processed, and operated by computers unlike continuous reals. By compiling the above baby steps, we can sketch a very rough idea of how this makes up the backbone of modern cybersecurity and cryptography. Among dozens of elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) algorithms, consider the elliptic curve Diffie–Hellman key exchange (ECDH).

Despite the intimidating term, ECDH is concerned with a simple problem elliptic curves can solve. Juliet and her secret suitor Romeo must exchange encrypted letters encoded with a password. While the couple must promise on a shared key, they have no means of communicating privately evading the deadly feud between their families. Thus their goal is to generate a private, shared key when all communication between them can be tapped. How can this be done?

Romeo and Juliet must find a way so that information on the open channel shows only a part of the secret key, and the actual key can never be deduced from the fraction of the key. The core idea lies in the repeated doubling of points. Denote $P+P := 2P$, $P+P+P = (P+P)+P := 3P$ and so on as multiplication by a number. Then, for very large modulus $p$, it is close to impossible to reverse-trace a point $G$ given the multiplication result $aG$. This difficult problem of finding the point before its multiplication with a number, or repeated doubling, is known as elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP).

ECDH involves the following steps. Romeo and Juliet each generate numbers $a$ and $b$, both of which they keep only to themselves. They would then publicly agree on a base point $G$, in which anyone can access. Then Romeo will compute $aG$ and send it to Juliet, and Juliet will send $bG$. After receiving the results, both parties use $a(bG) = b(aG) = abG$ as the shared key. While each $aG$, $bG$, and $G$ may be compromised, the eavesdropper knows nothing about $abG$ unless they can reliably backtrace $a$ or $b$ given the end result and the base point. This is impractical for any supercomputer if the prime $p$ is very large (however, quantum computers running a specific circuit called Shor’s Algorithm can crack ECDH with incredible efficiency; quantum computers of such practical computing power is yet to be built).

Thus was the bare minimum outlining the fascinating concept of elliptic curves. Both in practical cryptography and pure mathematics, the field is staggeringly giant in both width and depth of study.