A Bird's-Eye-View of the Lebesgue Integral

I discovered the world of measure theory and the Lebesgue (pronounced la-BEG) integral, when I was told that some functions cannot be integrated with Riemann sums. A more general integral, which has Riemann integrals as its subset, goes down an incredibly deep rabbit hole in the study of the reals.

First things first, integration is defined by either area under a curve or the inverse process of differentiation. For now, let us just consider the former, in the notion of the definite integral.

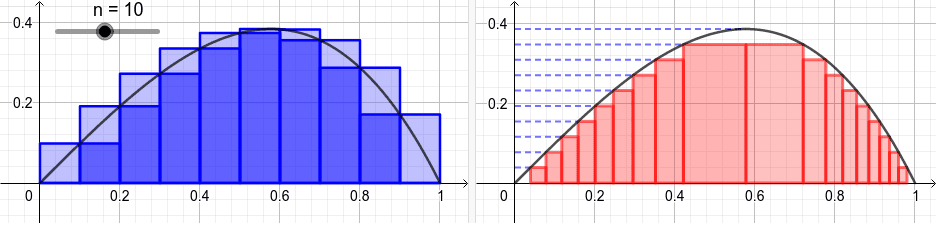

The idea of Riemann sums is to chop up the area under a curve into infinitely many intervals, with respect to the x-axis, then finding the sum. The idea of infinitely many chops is formalized by taking the limit.

In mathematical formalization, the Riemann sum is defined by \[\int^b_a f(t)dt = \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{b-a}{n} \sum^{n}_{i=1} f(a+\frac{b-a}{n} i)\] in a way that precisely shows its conceptual definition. There are numerous other formulations, all of which converge to the same sum. Except when they don’t.

Some functions show a mismatch between two different versions of the Riemann sum. In the same way a limit is undefined if the left-handed and the right-handed limit is distinct, the Riemann integral of some functions will simply be undefined. The Lebesgue integral resolves the problem and integrates a wider range of functions (but still not all functions $\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$). That said, all Riemaan integrable functions are also Lebesgue integrable, and the two integrals will have the same value.

Lebesgue Measure

Lebesgue integrals are defined using Lebesgue measure, written as $\mu (A)$ where A is a subset of $\mathbb{R}$. Informally, measure is a way to indicate the mass, so to speak, of a set. Imagine a rod made up of all real numbers in $(0,1)$; denote its mass by the (length) $1$. What should the mass of the set of points \(\lbrace0, 1/2, 1\rbrace\) be? Intuition tells us that points are massless, so any finite collection of points must have mass of 0. But consider \(S = \lbrace 1, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{4}, \frac{1}{8}, \frac{1}{16}, …\rbrace \) with infinite elements. Do they have mass of zero? Is $S$ any different from $(0, 1)$, as both sets have infinite elements?

If you have ever heard about the notion of countable and uncountable sets, it will be clear that the two infinite sets are a completely different animal. Mathematician Georg Cantor developed the relevant theory (shortly before going mad); you can read more here.

Formally, the Lebesgue measure of $A$ is the greatest lower bound (infimum) of the total length of (countably many) open intervals that cover $A$. It can be shown that $\mu(S) = 0$ by covering each and every one of its elements with an interval of length $\epsilon$. Since $\epsilon$ can be made arbitrarily small, the greatest lower bound of the total length of open intervals is zero. Grant Sanderson has a great visual representation here, as he always does.

With this definition, it is not difficult to prove some important ideas of measure. To list a few,

\[ \mu(\mathbb{Q}) = 0 \]

\[ \mu(\lbrace a_1, a_2, a_3, …\rbrace) = 0 \]

\[ \mu((a,b)) = b-a \] Furthermore, we say that sets $A$ and $B$ is equal almost everywhere and write $A=B$ $\mathrm{a.e.}$ iff $A$ and $B$ differ only on a set of measure zero. For example, \([0,1]=(0,1)\) \(\mathrm{a.e.}\).

Indicator Functions

This is a notational concept: the indicator function is defined by \(\mathbf{1}_{A}(x)=1\) if \(x\in A\) and \(\mathbf{1}_{A}(x)=0\) otherwise. It essentially indicates the presence of \(x\) in a set \(A\). Specifically, \(\mathbf{1}_{\mathbb{Q}}(x)\) is called the Dirichlet function. The Dirichlet function cannot be Riemaan integrated.

The Lebesgue Integral

Some slightly misleading thumbnails describe the Lebesgue integral as a horizontal Riemaan sum. There is some truth to this, and we will first observe the Lebesgue integrals of simple functions.

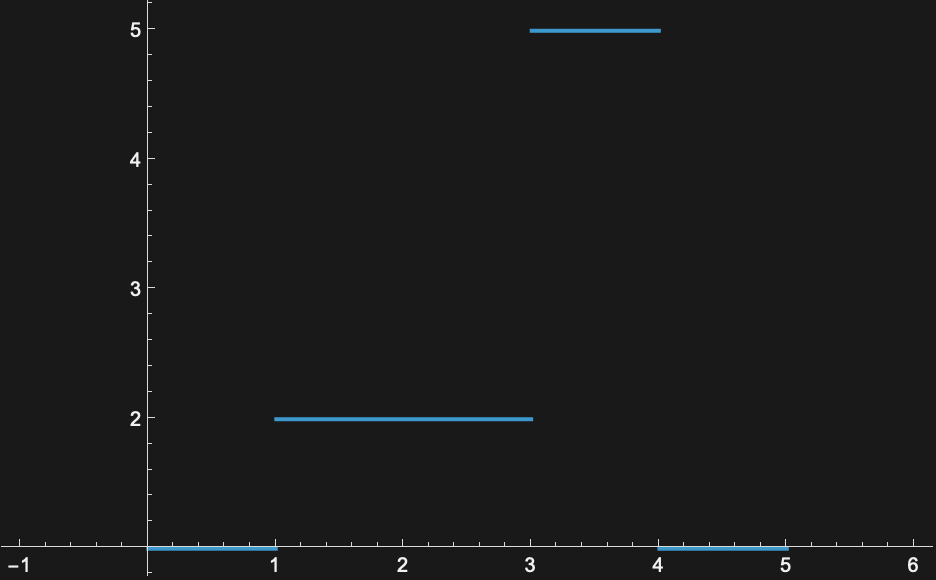

Simple functions, loosely speaking, take only a finite number of values per subset of its domain. They are of the form

\[\psi(x) = \sum_{k} a_k \cdot \mathbf{1}_{A_k}(x)\]

where for every region \(A_k\) is assigned the function value \(a_k\). Below is an example of a simple function, defined over \([0, 5]\).

How can we integrate a simple function? By the definition of definite integrals, we find the area under a simple function’s graph above the $x$-axis. Let us assume that the range of the function is positive, as of now. And, easily enough, we define \[\mathrm{Integral \space of \space \psi} = \sum \mathrm{height} \times \mathrm{base}\] \[= \sum a_k \times \mathrm{Length \space of} A_k\] \[= \sum a_k \cdot \mu(A_k)\] We are dividing the area into rectangular parts. But unlike the Riemaan sum, the Lebesgue integral is summed with respect to each $y$ value a function can take. More compactly, we write \[\int_S \psi(x) d \mu\] when we integrate the function over $S$. And that happens to be the sum above because \(\psi\) is simple. This tells us that function values with finite (or countably infinite) occurrences do not influence the integral, because its measure is zero. No matter the height value, the base component zeroes out the area of that set.

Luckily, the Dirichlet function is a simple function. Let us integrate the Dirichlet function over \((0, 1)\). \[\int_{(0, 1)} \mathbf{1}_{\mathbb{Q}}(x)d\mu\] \[= 1 \cdot \mu(\mathbb{Q}) = 0\]

The idea: approximate arbitrary functions with simple functions

The Lebesgue integral works for much, much more than simple functions. All Riemaan integrable functions are Lebesgue integrable. For non-simple functions, the idea is the bound the integral from below with a converging sequence of simple functions.

Take a Riemaan-integrable function \(f\) over \((a, b)\). Define a sequence of simple functions \(\psi_k\) such that \[\psi_k(x) = \sum_{i=1}^k f(a+\frac{b-a}{k}i) \cdot \mathbf{1}_{I_i}(x) \] where \(I_i\) is the $i$-th interval among $k$ equal subdivisions of $[a, b]$.

Aha! Then \[\int \psi_k d\mu = k\mathrm{th \space Riemaan \space sum}\] We define the integral of \(f\) to be the limit of the sequence above. Most often, it is trivial to prove that the supremum (least upper bound) of \(\int \psi_k d\mu\) is also its limit. It is also trivial to see that the two versions of the integral yield the same value.

Still more unintegrable functions

Even the Lebesgue integral cannot integrate every function \(\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\). First of all, divergent areas cannot be Lebesgue integrated – infinite is still infinite, Lebesgue or Riemaan.

The other demon arises from sets that have no Lebesgue measure! The axiom of choice lets us choose a subset of \(\mathbb{R}\) so that it is not measurable, such as the Vitali set. We have no idea what such a set would look like, yet we know of its existence.

Crazy world of math.